The evolution of graph computing in social networks and recommendation systems represents one of the most significant technological narratives of the past decade. What began as academic curiosity has matured into a foundational component of modern digital ecosystems, driving everything from friend suggestions to content personalization. The journey has been marked by both theoretical breakthroughs and practical innovations, reshaping how platforms understand and leverage interconnected data.

In the early days, social networks operated on relatively simple algorithms. Platforms like Friendster and MySpace used basic graph structures to map friendships, but the computational depth was limited. Recommendations were often based on explicit connections or rudimentary similarity metrics. The real turning point came when researchers and engineers recognized that the value wasn't just in the nodes—the users—but in the edges and their properties. This shift in perspective unlocked deeper insights into user behavior, preferences, and latent relationships.

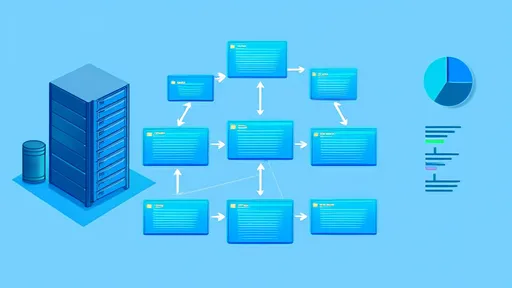

As social networks scaled to millions and then billions of users, traditional relational databases struggled to keep pace. The need to traverse complex networks efficiently led to the adoption of graph databases and specialized graph processing frameworks. Technologies like Neo4j, Apache Giraph, and later, distributed systems such as Apache Spark's GraphX, emerged to handle the computational load. These tools enabled platforms to perform sophisticated analyses, like identifying communities, detecting influencers, and mapping information flow across networks.

Parallel to these developments, recommendation engines evolved from collaborative filtering to graph-based methods. Early systems relied heavily on user-item interaction matrices, but they often missed the contextual nuances captured by graph structures. By incorporating social graphs, platforms could leverage homophily—the tendency of similar users to connect—to improve suggestions. For instance, if two users were closely connected and shared interests, recommending content from one to the other became more intuitive and effective.

The integration of machine learning with graph computing marked another leap forward. Graph neural networks (GNNs) and embedding techniques like Node2Vec allowed systems to learn low-dimensional representations of nodes and edges, capturing topological features in a way that pure algorithmic approaches couldn't. This fusion enabled more accurate predictions, from link prediction in social networks to personalized content recommendations based on multidimensional user graphs.

Today, graph computing is indispensable in social and recommendation contexts. Platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn use it to power features like "People You May Know" and "Jobs You Might Be Interested In." E-commerce giants like Amazon and Netflix rely on graph-based systems to suggest products and movies, often incorporating temporal and behavioral data to keep recommendations fresh and relevant. The real-time aspect has also become critical; streaming graph processing allows platforms to update recommendations instantaneously as users interact with the system.

Looking ahead, the evolution continues with trends like federated learning on graphs, which aims to preserve privacy while leveraging distributed data, and the use of knowledge graphs to incorporate external information into recommendations. As quantum computing advances, it may eventually offer new paradigms for graph processing, though that remains on the horizon. For now, the focus is on making graph systems more scalable, interpretable, and ethical—especially as concerns grow about filter bubbles and algorithmic bias.

In summary, the story of graph computing in social networks and recommendation systems is one of constant adaptation. From humble beginnings to its current role as a backbone of digital experience, it has continually evolved to meet the demands of scale, complexity, and user expectation. Its future will likely be just as dynamic, driven by innovations that we can only begin to imagine.

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025